The grandson of a man who painted the royals has written his biography in the hope of gaining him greater recognition. Charles Willis was an artist who won the big commissions but rarely got the accolades

CHARLES Willis died in 1963 aged 85 with an unfinished canvas before him. Few of his pictures were hung on the walls of his family home, apart from a few landscapes and family portraits.

But when his wife, Mabel, moved into a care home in 1995, his family discovered a large wooden box. It was packed with paintings, prints and newspaper cuttings.

“It had been compiled by my grandmother when my grandfather died and had been forgotten for more than 20 years. The most interesting things in the box were a large number of portrait prints of the Royal family,” says grandson Roger Stanyon, who lives in Startforth.

Willis’ career as an artist and illustrator spanned more than 60 years. His depictions of the Royal family before the Second World War were seen by many thousands of people and were used to illustrate fashionable journals, memorabilia and national newspapers.

However, outside the world of art collectors and auction houses, Willis is little known in the 21st century. That’s something his 83-year-old grandson wants to change.

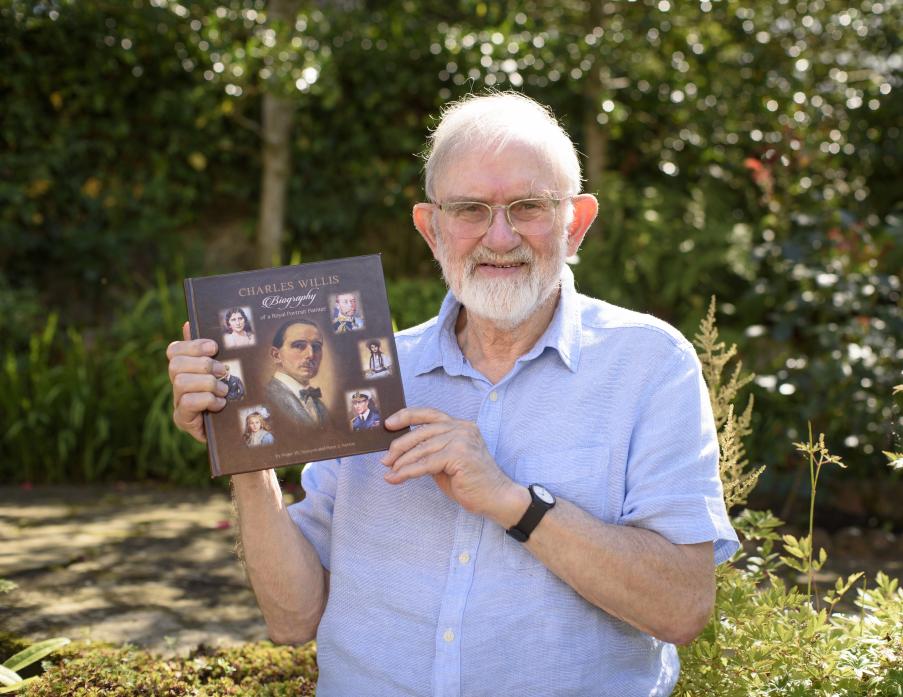

Though a great admirer of his grandfather’s talents, Mr Stanyon didn’t know what to do with his life’s work – until now. This month he has published Charles Willis, Biography of a Royal Portrait Painter. Its pages show the full range of the artist’s work – from watercolours and commercial pictures to portraits of George V and the Queen Mother to Queen Elizabeth II in her youth.

Mr Stanyon says: “He was well known in the 1930s as an artist but no one has really heard of him today. That’s one of the reasons why I wanted to publish the book. I want people to know more about my grandfather – artists just disappear.

“I remember him where I grew up in north London. He was in his 70s by then and wasn’t too well, but he was still working full out. He was painting intricate details with such skill and quickly – his work was always about meeting deadlines. He could sketch, use pen and ink, watercolours, oils – everything.

“His commercial work sometimes appears at auctions and can sell for £3,000 to collectors. Occasionally, one of his royal portraits appears and those can go for £20,000 to £30,000. One large portrait of King Edward VII is currently on the market for £35,000.”

Willis was born in 1878 in Lincoln. From a poor family, his skill as a young artist shone through and he was given a scholarship at an art school. He started a studio but soon after joined the South Nottingham Hussar Regiment. An ankle injury prevented him from being called up in the First World War. It was a blessing in disguise and he became a self-employed artist, producing watercolours and paintings for adverts, from cigarettes to biscuits.

His work was used to decorate tin boxes around the time of the First World War with images of Lord Kitchener and George V, along with war heroes of the time.

Willis then began to concentrate on portraiture. Some of his finest portraits are of his young family, one showing his blooming wife Mabel, who was pregnant. A miniature of his daughter, Nita, in 1919 when she was seven. Nita died just ten years after sitting patiently in front of father’s easel but the picture is regarded as one of his best. Major auction houses recently estimated its worth at £10,000.

In 1924 his family moved to London where he earned a good living painting illustrations for glossy magazines, children’s books, advertisements and posters for cinema and West End plays. He also had a sideline producing saucy postcards.

Willis could also be temperamental.

Once he painted a well-to-do woman who he didn’t much like. The work wasn’t going as planned and she turned up so late to a session that the light was gone. Willis smashed the painting as she looked on.

He charged £200 for portraits of businessmen, dignitaries and royalty. These included Princess Marina, the Duchess of Kent before her marriage to Prince George, the fourth son of King George V. The wedding is still remembered for its glamour and the picture was used in countless publications and on memorabilia.

In 1936, he was commissioned to paint portraits of Edward VIII in preparation for his future coronation. Willis was due to depict Wallis Simpson but this idea was scrapped after Edward abdicated so he could marry her, creating a national scandal. When Willis was asked to paint the Royals for a ceremony in which they would be wearing official robes, he was allowed a session at Buckingham Palace but it was the staff not the royals who modelled the clothes. However, he was given a short sitting with the king and queen.

Willis’ efforts won their approval but such a face-to-face meeting was rare.

Normally he would get a portfolio of photos to work from, such as when he painted the Duke of Edinburgh and Princess Elizabeth in 1947 ahead of their marriage. Images of his work from that period are still used by the press today.

What Willis did during the Second World War is a mystery. It is thought he probably worked on anti-Nazi propaganda posters for the Government.

He continued to paint but failing health meant he turned down a portrait commission for the Queen’s coronation in 1953. He was 75. A few years later the family moved to Middlesex and his portraiture faded from the public view, his wife packing the pictures into the large wooden box after he died.

Mr Stanyon’s friend, Peter Norton, helped to write the biography after seeing the paintings first hand.

Mr Stanyon said “Peter is an artist and when he saw my grandfather’s work said we really should do something with it. So we did.”

In the book, Mr Norton writes: It is a great shame that he never won the accolades for his work that many of his contemporaries and friends achieved. The higher echelons of the art world in the 20th century rarely approved of commerciality in art and perhaps that is why Charles was never awarded any letters by the art institutions and societies.”

Mr Stanyon added: “This book is printed in memory of him and his work. I am very proud of him.”