In an occasional column, Dorothy Blundell takes a sideways personal look at what goes on behind the scenes at The Bowes Museum where she is a volunteer

IT is a truth universally acknowledged that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of... staff.

Forty years after Jane Austen almost wrote this opening to her 1813 novel about Darcy and Elizabeth Bennet, the story of John Bowes and Josephine Coffin Chevallier, proved the sentiment held true. The co-dependence of the ‘Upstairs, Downstairs’ worlds of the 19th and early 20th century continues to inspire TV series and film-makers. Indeed, John himself was the result of a liaison between the 10th Earl of Strathmore and one of his estate workers.

John was brought up as a gentleman’s son and so assumed the mantle of heading a household and managing servants quite naturally. For actress Josephine, marriage to a wealthy aristocratic Englishman was huge social elevation which must have taken her some adjusting to. Perhaps because of this, it was largely John who oversaw control of the detailed running of their home at Streatlam as well as their Paris townhouse and country chateau. And he was a stickler for detail.

Two months before arriving at Streatlam, Bowes would deluge his agent, Ralph Dent, with letters giving instructions for his and Josephine’s transport, plus their personal servants, coachman, groom, four horses, carriage (sometimes two) and dogs.

There were orders about all sorts of things from bed curtains (drawn by cord, not by hand), to food (poultry sent over from France as they made “better eating”) and drink (tea is Flowery Pekoe and coffee is half moka and half East Indian mixed). Even winding the clocks and oil in the lamps were included.

Mr and Mrs Bowes employed a number of English servants in their homes in France. The museum archives has many letters from John to Dent asking him to find yet another housemaid or footman or lady’s maid for Josephine. The latter should not be “a dressy or fine person like most English maids are, but a plain respectable person”. Male servants were required to be “intelligent, quiet and sober”.

In her biography of the couple, Caroline Chapman relates anecdotal evidence that when staying at Streatlam, Josephine would hide money about the house to see if it was stolen and that she insisted the carriage was ready at the front door every day in case she wanted to go for a drive.

Apart from the culture difference (“French butlers are not accustomed to dawdle about in the housekeeper’s room like the English are”), there were also language difficulties. Josephine did speak a little English but communications between resident servants and those who travelled with the couple were relayed through John.

When in 1861 they brought over a seamstress from France, she was said to be, “a very quiet, respectable old person but a terrible talker”. John added: “However as they [other staff] will not be able to understand what she says, she is not likely to trouble them much with that.” In 1867 John rather despairingly asks Dent if there could be someone at Streatlam who could speak French.

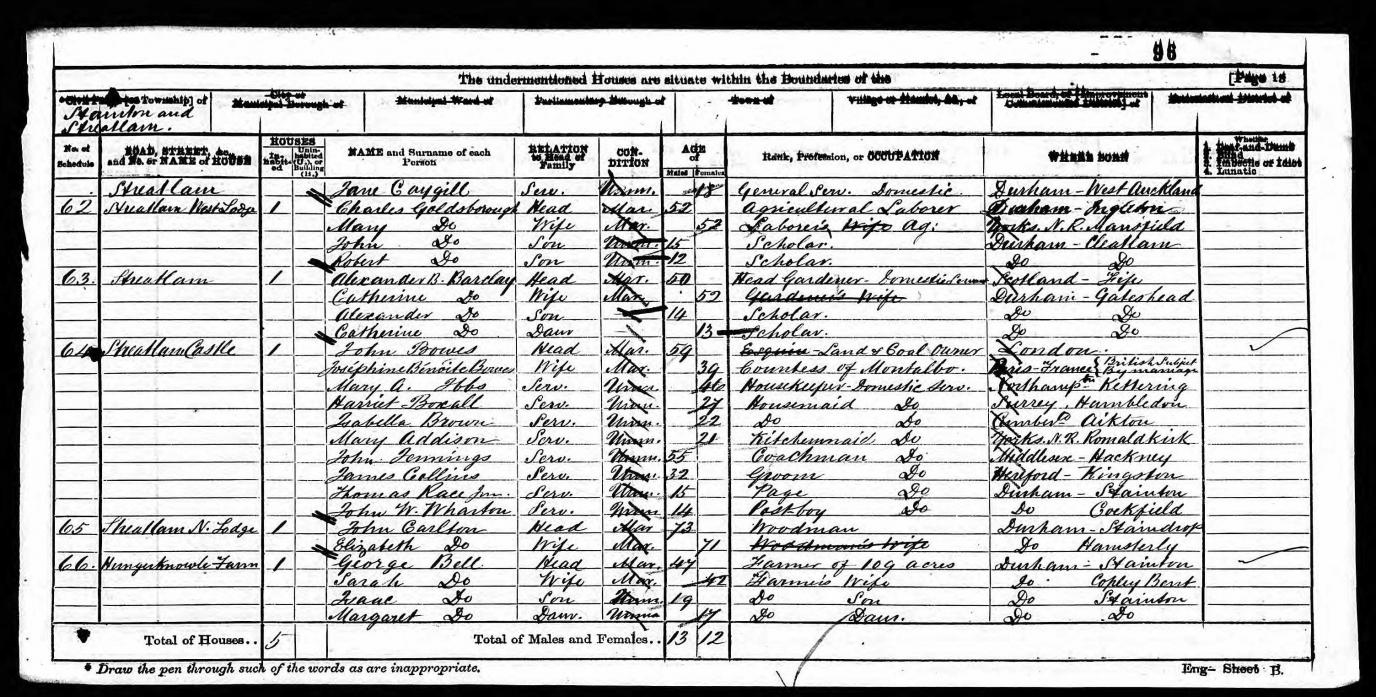

The census of 150 years ago lists eight servants at Streatlam Castle. This is the only census in which John and Josephine appear (interestingly, Josephine, born in 1825, has knocked seven years off her age). June Parkin, a volunteer at the museum archives, delved a little deeper and discovered fascinating insight into the servants’ lives. Most were not from the local area. The two women stayed in domestic service, but the two youngest escaped. Thomas Race was a page (trainee footman) and John Wharton, a postboy. Race was born in Stainton in 1856, the son of a gardener, and grew up to be a policeman and father of four in Eccles, Lancashire. By 1911 he had retired to Bartisland, near Halifax and was a poultry farmer. He died aged 81. Wharton was born in Staindrop in 1857. He worked for a time as a miner and, aged 24, he was living in Newcastle with a job as a porter. By 1891 he had returned to Barnard Castle and was living in Baliol Street with his wife Mary, a son and a daughter, and working as a whitesmith (tin worker).

In 1872 and 1873 John was beset by staff problems. He instructed Dent to find a butler in England and to impress upon him that “though this is a quiet place, it is one where he would have a great deal to do... he must do things in a very quiet and stylish manner and exactly according to our directions and habits”. When a new footman is sent across from England, Bowes comments: “He has only the sight of one eye, he wears a wig, has very large feet and hands and seems to have some defects in his speech and appears altogether an unhealthy subject.”

The most intriguing story relating to Bowes and his servants is from the saddest chapter of his life: his divorce proceedings against his second wife, Alphonsine, whom he married in 1877 three years after Josephine’s death. In early 1884 Bowes told Dent about Alphonsine’s infidelity with Monsieur Millet (and “two or three more”). Bowes’ valet, Joseph Smith, had revealed that he had seen Alphonsine and Millet together in “an indelicate and indecent attitude” at rue de Berlin, their Paris townhouse, and “about a fortnight later in the act of adultery”.

When the case opened in London at the beginning of February 1885, there were six servants from rue de Berlin in court, presumably ready to give evidence on behalf of their employer. Lawyers for the second Mrs Bowes kept delaying matters until Bowes, sick at heart and in body, and also aghast at public revelations of his private life, agreed to compromise. He died later that year with matters unresolved.

It was an unjust ending for a man who had throughout life sought to treat others fairly. He rewarded loyal and good service with kindness and consideration and he felt affection towards long-term employees.

That John Bowes, like Darcy from Pride and Prejudice, rose above social norms to marry Josephine, the woman who won his heart, is a matter of record.

And the 1871 census is a record which helps us remember that in the Bowes’ story there were also those who played their part “below stairs”.