In her regular column, Dorothy Blundell takes a sideways look at the collections of The Bowes Museum where she is a volunteer. This week, she pens a whimsical open letter to actor, novelist and screenwriter Julian Fellowes...

DEAR Julian,

following your well deserved success with Downton, could this be your next project? Essentially, it is a love story wrapped up in an aristocratic family dynasty and set against the grimy, war-torn streets of 19th Paris contrasted with the beautiful backdrop of rural northern England where – incongruously – a palatial French château is the focal point.

The hero is born of noble blood, but with the stain of illegitimacy. He is a saucy young man who matures into an astute businessman with a strong sense of public duty, and uses his vast wealth with an uncommon benevolence.

The heroine is a pretty young Parisian actress of slight build and quick temper, but with a generous and kind heart. She’s no gold-digger, though she readily climbs the social ladder that his company affords, and obviously adores her broad-shouldered, handsome beau, calling him “Papa”.

This is the story of John and Joséphine Bowes. Their lives together and their enduring legacy of the magnificent museum they left behind are a rich source of material for a film or television adaptation. Their love transcended 19th century class barriers, for our hero marries his French mistress – as his ennobled father before him similarly married a commoner who had been his wife in all but name for ten years.

Who would be your choice for the title role?

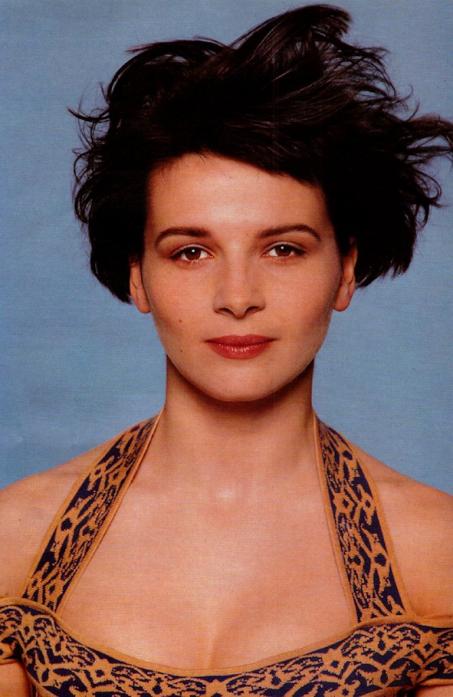

Perhaps Hugh Jackman (from his days as Wolverine when he sports John’s mutton chop whiskers). And his young wife? Perhaps French-born Juliet Binoche, with her dark hair, large eyes and ability to portray deceptive inner strength.

Here’s a thought: the screenplay could open with a photograph of John as an old man. He is seated at a small table on the terrace at his home in Streatlam (this actually exists).

His white whiskers are neatly trimmed and he wears a suit, bow tie and a black hat. In his hand is a stick which he needs to help him walk. There is an air of sadness about the slope of his shoulders and his gaze is melancholy: a man tired of life.

He is remembering an earlier time. Cut to the contrasting image of a portrait of a middle-aged John that was painted by Feyen in 1863. John’s expression radiates energy and bonhomie. He is seated on a rock cradling his shotgun, bagged game birds and a small dog at his feet. It’s the classic pose of a country squire.

In our imagination, the cameras would show this portrait dissolving into “real life” and Hugh Jackman – playing John Bowes – standing up to dispense with all the props and get on with the business at hand. It was customary for portrait-sitters to be shown surrounded by items which reflected their interests, but John’s wish to be seen as a sportsman was curious given that such pursuits of the idle rich played very little part in his life.

He was more interested in public duty and managing his assets in coal, shipping and land while running his theatre in Paris and indulging his passions for collecting art, horses and racing.

It’s April 1847. Enter Madame Delorme, otherwise known as Joséphine Coffin-Chevallier. John Bowes, aged 35, is instantly smitten by the 22-year-old beauty with her disarmingly kittenish smile. He calls her “Puss” and even though their loving marriage (they wed in 1852, five years after meeting) was to prove childless, between them, they give birth to The Bowes Museum.

She is the driving force of the project, and he, the money. Though often apart, John writes to “Puss” every other day and readily indulges her desires for expensive designer dresses and lavish furnishings for their homes in Paris and Louveciennes. When she goes out to paint, he usually goes with her.

The year of 1852 is also significant as John’s horse, Daniel O’Rorke, wins the Derby and the following year, West Australian wins the Triple Crown, the first horse to do so. Imagine all those scenes of parties and celebrations. Joséphine goes with him to Longchamps, the racecourse in Paris, when it opens in 1857, and to Goodwood racecourse in Sussex.

It was all part of the happy couple’s love of life and embracing the finer things it had to offer during the Second Empire (1852-1870). Though we do not know for certain that they rubbed shoulders with French royalty, it seems quite probable that they did.

Perhaps they socialised at the opera, or at the races, or at one of the many lavish balls given by Napoleon III and Empress Eugenie at the Tuileries.

Among significant scenes will be the couple’s many shopping sprees for artworks and artefacts, amassing 15,000 items in only a few years, including visits to the Paris Exhibition of 1867 where they first saw the Silver Swan. This lifelike musical automaton eventually becomes the museum’s most famous and well-loved exhibit. And when France goes to war with Prussia, they shelter in England and spend months fretting about the fate of their collection, which does survive intact.

The movie draws to a tearful end with a scene from November 27, 1869, and the laying of the museum’s foundation stone by Joséphine, whose fragile health by then is failing. She bravely, but feebly, taps a stone with a silver trowel.

Juliette – as Joséphine – lip trembling, declares: “I lay the bottom stone and you, Mr Bowes, will lay the top stone.”

Alas, Joséphine dies aged 48 in 1874, when the museum building was still incomplete. John’s heart is broken (cue violins and tissues) and he does not know how he can carry on.

Final scenes cut to the opening image of John as an old man and we see how he does indeed carry on. He might be tired of life but he’s determined to be steadfast until the end (his family motto). Our hero honours his and Joséphine’s dream of bringing a French chateau to Barnard Castle as a home of wonderful works of art that delight and educate the public.

When he dies aged 74 in 1885 it takes another seven years before the doors to the museum finally open. But the story of the museum goes on. It is still welcoming visitors to explore the thousands of art treasures within. Close up on the Silver Swan in motion. End credits roll... and fade to black.

So, Lord Fellowes, what do you think? Here are all the ingredients you could possibly want to create a marvellous drama.

There is glamour with royal banquets and lavish period costumes, there is conflict with the ugliness of war and famine. There are loyal Bowes servants, including a housekeeper whose game pie is legendary, and there is heartbreak. But primarily, there is love – the love of John and Joséphine for each other and their love of art and sharing it with the wider world.

Perhaps you could call it Swanton.